After the rise of Christianity in Ethiopia in the fourth century, the Jews who refused to convert were persecuted and withdrew to the mountainous Gondar region where they made their homes for more than 2000 years. In the tenth century, they rose against the Axum dynasty led by Queen Judith who overthrew the “negus” (king) and sought to eradicate Christianity throughout the country. She is not forgotten to this day. Later, with the establishment of a new royal dynasty, the Jews of Ethiopia enjoyed great influence for some 350 years often acting as the balance of power between the Muslims and Christian forces.

The return to power of the ancient Axum dynasty in 1270, marked the beginning of 400 years of war and bloodshed which ended in the 17th century with the final end of Jewish independence. After the final battle when the Jewish forces were finally defeated “Falasha men and women fought to the death from the steep heights of their fortress…they threw themselves over the precipice or cut each other’s throats rather than be taken prisoner. (Christian Ethiopian Chronicles) The Jews now faced years of suffering, their lands were confiscated, and for a period were forbidden the practice of their religion. The wars, the bloodshed and the glory were over, but persecution in various forms continued.

Modern Contact

The first modern contact with the now oppressed community came in 1769 when the Scottish explorer James Bruce stumbled upon them while searching for the source of the Nile River.

Missionaries in the nineteenth century drove many to begin a doomed trek to Jerusalem, but over the years others were successful.

In the early years of the twentieth century, only a small trickle made their way to Israel. In 1954, the Jewish Agency (www.jafi.org) sent an educational emissary to Beit Israel with the task of training groups which would eventually travel to Israel for study and return home as teachers of Hebrew and Jewish studies in their villages. The first group arrived at Kfar Batya in 1955 and these operations continued for a number of years. Other Jewish groups offered aid, welfare, medical care and education including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (www.jdc.org) which commenced welfare operations in 1983.

During the reign of Haile Selassie (1930-1974) the Jews of Ethiopia were treated with indifference but their inability to own land was coupled with the scorn of their neighbors who attributed to them every misfortune which befell them. In the struggles following the deposition of Haile Saleassie, an estimated 2,500 Jews were killed and 7,000 rendered homeless. From the end of 1977, small groups of Jews began to flee, joining refugee villages on the other side of the Sudanese border. Those caught trying to flee Ethiopia were arrested and tortured.

Claiming that Hebrew was being taught in preparation for emigration to Israel, the governor of Gondar confiscated Hebrew books, the practice of religion was forbidden, Jewish schools and synagogues closed and students caught talking to tourists were questioned and imprisoned. Travel was restricted and a Jew without a travel pass was assumed to be trying to escape and liable for imprisonment. But, the exodus continued. Within three years, there were hundreds of Jews in Sudan living in terrible conditions.

Pressure from world Jewry increased, the government of Israel pledged itself to save the Jews of Ethiopia and the Jewish Agency shifted its policy from quiet diplomacy to call for a worldwide campaign to publicize their plight.

Operations Moses and Solomon

In secret operations beginning in 1980, Israeli operatives were able to smuggle hundreds of Ethiopian Jews through Kenya to Israel. By the end of 1982 there were 2,500 Ethiopian Jews living in Israel and throughout 1983, 1,800 left Sudan over land. Recognizing the need to move more quickly, the Israelis began to use a nearby air strip to land Hercules transport planes which could each bring out 200 immigrants per flight. Utilizing a variety of routes, a total of 8,000 Jews had reached Israel by late 1984.

However, it was clear that the large numbers of Jews crossing into Sudan exacerbated the already horrific conditions in the camps. On November 21, Operation Moses began. Refugees were bused out of the refugee camps to a military airport near Khartoum where they were flown directly to Israel under a blanket of complete secrecy.

When news leaks ended the operation in January 1985, 8,000 Jews had been brought to Israel, leaving behind about 1,000 Jews in Sudan and thousands more in Ethiopia. Initiated by Vice President Bush, a CIA sponsored follow-up mission called Operation Joshua brought an additional 800 Jews from Sudan to Israel.

Operation Moses separated many from their loved ones and more than 1,600 “orphans of circumstances” separated from their families began new lives in Jewish Agency Youth Aliyah villages, learning Hebrew and becoming acculturated not knowing the fate of their parents, brothers, sisters and loved ones. Others took the first difficult steps in Agency absorption centers where they learned to live in a modern society.

The Fulfillment of a Dream

The grim prospect of thousands of Jewish children growing up in Israel, separated from their parents almost became a reality. Nothing could be done to persuade the Ethiopian governor to increase the trickle of Jews leaving Ethiopia in the years between Operations Joshua and Solomon. But, in 1990 the governments of Israel and Ethiopia reached an agreement allowing family reunification, which was gradually broadened to allow others to leave for Israel.

As the news spread that Jews were able to leave, thousands left their homes in Gondar and made their way to Addis Ababa. At the time of renewal of relations between the two countries there were 2,500 Jew in Addis. They were cared for by American organizations such as the JDC and prepared for Aliyah by the Jewish Agency. A school was set up for the children which eventually served as many as 5,000 students. Family heads were offered work and each family was given a monthly subsidy for living expenses. Medical facilities were established.

It became clear that the Ethiopian government had decided to limit aliyah to 1,000 per month. Quotas were determined according to time spent in Addis, in Sudan, the sick, the elderly, religious leaders etc.

By the end of 1990, the economic and political situation in Ethiopia had deteriorated with struggles between rebels and government intensifying daily. Aliyah and aid workers were concerned with the dangers of the transition period if the rebels gained ground. Representatives of the Jewish Agency, JDC, ministries of the government of Israel and the IDF began secret preparations for an emergency airlift and absorption of more than 14,000 Jews.

JDC took responsibility to institute an emergency call-up system, JAFI to organize the collection points and transfer to temporary housing in Israel. The Israel airforce and army would provide logistical support and El Al would also supply staff and airplanes.

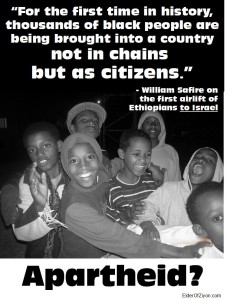

In late May, as insurgents closed in on Addis, the plan was put into action. There were very special passengers on the first plane to leave Israel en route to Ethiopia on Friday, May 30, 1991 – 50 veteran Ethiopian immigrants mobilized to help bring their brothers and sisters home. The last plane to leave 36 hours later, an IDF 707 bore the organizers and workers of the operation.

Although the operation was kept secret, rumors of the arrival of thousands of Jews from Ethiopia spread by word of mouth. Thousands of Israelis flocked to the temporary absorption centers set up in hotels and hostels to welcome the newcomers, witnessing the joy of reunion between long separated family members.

The Jews of Quara

Hundreds of Jews from the remote region of Quara were cut off from Addis by the advance of rebel forces and unable to join Operation Solomon. When permission was finally granted, Jewish Agency emissaries made the difficult journey over land to the northern region on the Ethiopian/Sudanese border. As it was impossible to bring the Jews of Quara directly to Addis, an alternate route was chosen. Groups of Ethiopians made their way on foot to a collection point accessible to trucks and then on to Addis and Israel. In Addis, they were provided with medical staff and with financial assistance by the JDC. The first flights left Addis on September 15, 1991, and in the nine months that followed, 4,500 Jews followed this route. Jews from Quara continue to arrive to this day.

The Authenticity of the Ethiopian Jewish Community

As early as the 16th century, Egypt’s Chief Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Avi Zimra (Radbaz) declared that in Halachic (Jewish legal) issues, the Ethiopian community was indeed Jewish. In 1855, Daniel ben Hamdya was the first Ethiopian Jew to visit Israel, meeting with a council of rabbis in Jerusalem concerning the authenticity of the community. By 1864, almost all leading Jewish authorities, most notably Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer of Eisenstadt, Germany, accepted the community as true Jews. In 1908 the chief rabbis of 45 countries had heeded Rabbi Hildesheimer’s call and officially recognized the Ethiopian Beta Israel as fellow Jews.

In reaffirming the Radbaz’s position centuries before, Rabbi Ovadia Yossef, Israel’s Chief Sephardic Rabbi, stated in 1972, “I have come to the conclusion that Falashas are Jews who must be saved from absorption and assimilation. We are obliged to speed up their immigration to Israel and educate them in the spirit of the holy Torah, making them partners in the building of the Holy Land.”

In 1975, the Israeli Interministerial Commission officially recognized the Beta Israel as Jews under Israel’s Law of Return, a law designed to aid in Jewish immigration to Israel, on the basis of a 1973 decision by Rabbi Yossef. The community was ready to come home.

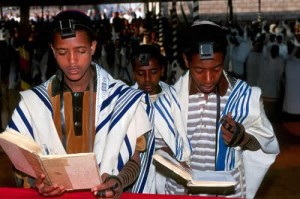

Indeed, the Ethiopian Jews were strictly observant in pre-Talmudic Jewish traditions. The women went to the mikvah, or ritual bath, just as observant Jewish women do to this day, and they continue to carry out ancient festivals, such as Seged, that have been passed down through the generations. The Kesim, or religious leaders, are as widely revered and respected as the great rabbis in each community, passing the Jewish customs through storytelling and maintaining the few Jewish books and Torahs some communities were fortunate enough to have written in the liturgical language of Ge’ez.